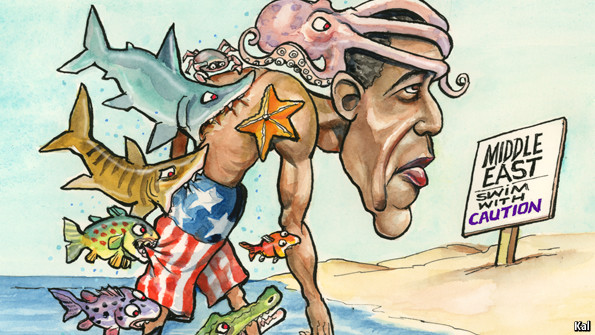

The arab street hates Barack Obama. Many angry Egyptians accuse him of secretly supporting the Islamists who ran the country until July. Many others (equally angry) accuse him of backing the generals who overthrew the Islamists. Both charges cannot be right. Indeed, neither is. Yet loathing of Mr Obama runs wide and deep in the Muslim world, though he came to office vowing to mend relations with it, after the hubris and blunders of his predecessor.

When you are the commander-in-chief of a superpower, people often assume you are more powerful than you really are. To many Islamists the Egyptian army’s ousting of their leader, ex-President Muhammad Morsi, simply has to be America’s handiwork. Islamist posters in Cairo depict Mr Obama as a wicked pharaoh, leading Egypt’s military strongman, General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, by a dog-leash. To such folk, evidence of American perfidy is all around: from comments by John Kerry, the secretary of state, that the army was merely “restoring democracy”, to Mr Obama’s reluctance to suspend military aid.

In contrast, to many Egyptians who back the generals, events have unmasked Mr Obama’s warm words about Arab democracy as a plot to empower Islamists, with an eye to dividing and weakening their homeland. Pro-army posters depict Mr Obama as a terrorist sympathiser with a bin-Laden-style beard.

Back home in America, too, Mr Obama is denounced in stereo. How feckless this president is, thunders a cross-party chorus of congressmen and pundits, urging him to suspend military aid to Egypt, lest America be complicit in a moral disaster. But oh, how reckless this president is, counters a camp that favours Realpolitik. The realists, both Republican and Democrat, want Mr Obama to hold his nose and back Egypt’s generals, to ensure stability on Israel’s borders and help contain radical Islam.

Syria inspires similar cacophony in Washington. Foreign-policy grandees call Mr Obama rash for saying that Bashar Assad had to go without first figuring out who might replace him, and for vowing to act should the regime use chemical weapons: a “red line” tested afresh on August 21st by allegations of horrific gas attacks on civilians near Damascus (prompting cautious White House calls for a UN investigation). A rival, bipartisan camp calls Mr Obama weak and timorous for failing to arm Syria’s rebels.

As noted earlier, these duelling critics cannot all be right. Lexington would go further. Anyone who accuses Mr Obama of picking winners in the Middle East, or urges him to do so, misunderstands the president. Mr Obama is not in the business of taking sides in foreign conflicts. He is profoundly cautious about wielding American power, and even about defending values that—when the going was easier—he hailed as universal.

In 2011, as the Arab spring reached Cairo, Mr Obama heaped praise on Egyptians for seeking “nothing less than genuine democracy”. He quoted Martin Luther King and praised largely peaceful protests for “putting the lie” to the idea that justice is best gained through violence. He lauded the Egyptian army for refusing to fire on civilians. Two-and-a-half years later, events leave less room for presidential lyricism. On August 15th Mr Obama rebuked the same army for its brutishness, saying that Egyptians deserve better. Then he chided Egyptians for their conspiracy theories about him, such as his supposed support for both Mr Morsi and his foes. Blaming America will “do nothing” to build a peaceful, democratic, prosperous Egypt, he scolded.

Such chilly rationality will not placate Arabs whose blood is boiling. From Syria to Egypt and beyond, partisans yearn to crush old rivals or sectarian foes once and for all. Mr Obama’s response is to dispatch envoys to preach the merits of negotiation and inclusion. On August 19th the defence secretary, Chuck Hagel, declared America’s influence in Egypt “limited”. General Martin Dempsey, chairman of the joint chiefs, has warned against picking “one among many sides” in a Syrian war whose underlying causes cannot be resolved by American military force.

Not every crisis is a quagmire

Such coolness matches the mood of many Americans. Fewer than one in four claims to be following events in Egypt very closely. According to a new Economist/YouGov poll, only 12% think Mr Obama has a clear strategy for Egypt, but that will not cost his party many votes. Television images of Arabs slaughtering Arabs—even of children convulsing after alleged chemical attacks in Syria—have not stirred American viewers very much.

During the Balkan wars of the 1990s several mid-ranking officials resigned in protest at American inaction, notes Robert Satloff of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, a think-tank. Mr Obama’s hands-off approach to Syria, Egypt and elsewhere has not led to a similar walk-out. At the same time the president has bought himself credit in Congress and in Washington by embracing Israel more closely in his second term, and by letting Mr Kerry work on restarting Israeli-Palestinian peace talks. As a result, Mr Obama is shielded from grumbling about Syria.

Memories of overreach in Iraq and Afghanistan also help explain the national mood of coolness towards the Muslim world. But lessons from history can be over-learned. Frederic Hof, a former Syria point-man at the State Department, now at the Atlantic Council, sees an “Iraq syndrome” within government, and a prevailing view that America will botch any intervention it tries. Yet air strikes might slow or halt some Syrian massacres.

Contrary to the wild accusations against him, Mr Obama is not the hidden hand behind the Middle East’s tumult. In truth, he hates to take sides, fearing that any fresh entanglements may prove as bloody and costly as George W. Bush’s. But sometimes sides should be taken. Detachment can also be a sin.